texts, notes and essays connected to my practice….

Diving for Pearls: The Work of Órla Bates

Essay by Ann Mulrooney

Written for Sync Shift, solo exhibition

Wexford Arts Centre / MAKE Curate Programme, 2025

This essay was written by curator Ann Mulrooney as part of my solo exhibition Sync Shift, and reflects on the development of my drawing practice since 2020

I first met Órla Bates in 2020. I say ‘met’, but really it was a virtual meeting -I had been commissioned by Artlinks to deliver a series of online workshops on practice-based research for artists based in the South-east during Covid. The workshops were about tapping into the creative process, understanding what feeds our practice and recognising the sense of resonance when we find what’s right for us. I asked the participants to think of their current practice as a form of hands-on research, and, working backwards, to formulate what it was their research question might be. In academia, the research process is about putting forward a new, original hypothesis or idea, and then investigating if it is true or not. The hypothesis or idea is framed as a question, enabling clear choices or decisions about research methods, processes and approaches, and an ability to discount what is superfluous. Artistic practice-based research is much broader and more open ended than academic research, but it is still about having a core idea (or belief or feeling), and investigating the truth of that. Very often, the core idea is complex and multi-faceted and possibly even wordless – and so the answers, the practice, the outcomes, are also often complex, and intertwined, and hard to explain or represent simply. Even across an internet connection, I could see how intensely Órla connected with this idea of her practice as a research method. The workshops seemed to have coincided with a period of fierce internal interrogation for her, as she sought to bring her own artistic practice and outcomes into a different balance with her inner world.

Scroll through images of her work since then, and it is like looking at a process of disintegration. The strong, graphic figurative quality of earlier work, informed by her studies as a printmaker, has gradually dissolved into the page, leaving behind sibilant echoes that ripple across the surface. The marks appear both unstructured and deeply intentional, felt rather than seen; the paper becoming a site for presence rather than representation.

I am struck by a visual similarity to Japanese ink painting in her more recent work, something to do with the exquisite balance and sureness of what remains captured on the surface of the page. Her marks have become less a visual description and more an event—improvised, responsive, and alive. Derived from Zen Buddhist principles, sumi-e, a type of ink painting, emphasises simplicity, spontaneity, and the integration of the artist’s inner state with their brushwork. The aim is not to render objects realistically but to capture their essence in a single, fluid gesture. The practice involves deep breathing, emptying of the ego, and the cultivation of wabi-sabi—an appreciation of the beauty of impermanence, imperfection, and incompleteness. Sumi-e operates on the principle of mu or “nothingness,” not as a nihilistic void but as an open field of potential, the awareness that exists prior to knowledge or experience. The blank white of the paper is as important as the black of the ink. The brushstroke becomes a trace of the artist’s presence—an embodied moment of being, not a record of the thing itself.

When Órla and I speak about this, she recognises this quality in the work, though only in hindsight - although she had an awareness of Sumi-e, it was not an influence in her work, and only much later in her journey did she look into the practice and realise the similarities with what she had been quietly pursuing. For a number of years now, she has been using meditation as a drawing tool, a means of escaping her graphic ability to capture what she sees, and instead to dive deeper down, unearthing what it is she feels, pushing past her conscious tendencies to order and depict and instead allowing her body to respond and express. Rather than using the hand alone as a drawing tool, she incorporates makeshift drawing implements, full-body gestures, movement and breathing rhythms into her mark-making, always grounded in her extensive reading and visual research.

Artists such as Rebecca Horn and Heather Hansen have explored similar territories, using implements and the body as a conduit for mark-making. Hansen’s Emptied Gestures (2013), for instance, consists of large-scale charcoal drawings made through dance-like movements on the floor. These works are traces of the body in motion, capturing the ephemerality of lived experience. Likewise, Bates’s process increasingly relies on allowing her body to lead the mark, resulting in drawings that are intimate yet universal, shaped by rhythms of breath and impulse. The practice of authentic movement—a technique developed in dance therapy where the body moves from an internal impulse without predetermined form—also resonates with her drawing process. Her marks often emerge in response to subtle internal cues, bodily memories, or somatic feedback. The resulting works are not only visual but also corporeal, inviting the viewer into a multisensory space where perception and sensation converge.

Her practice has more than a passing similarity to dance; particularly in her collaborative work with UK artist Joanna Leah, which has had a formative influence on her practice since their first collaborative drawing experiences in 2022. She describes their experience of working together as a method of feeling their way towards a shared rhythm, working within parameters of movement and language that they have set in advance. I remember also her excitement having seen Jeremy Shaw’s work, Phase Shifting Index, a multi-channel audiovisual installation consisting of seven autonomous but simultaneously replaying video works, each screen depicting different groups performing different movement or song-based rites, a seeming cacophony that slowly shifts and coalesces into deep sense of shared rhythm, an experience that gave her the title of this exhibition, Sync Shift, as a description of what it was she was searching for through her practice. Like Bates, Shaw’s work is also concerned with accessing different states of awareness and the search for transcendental experiences.

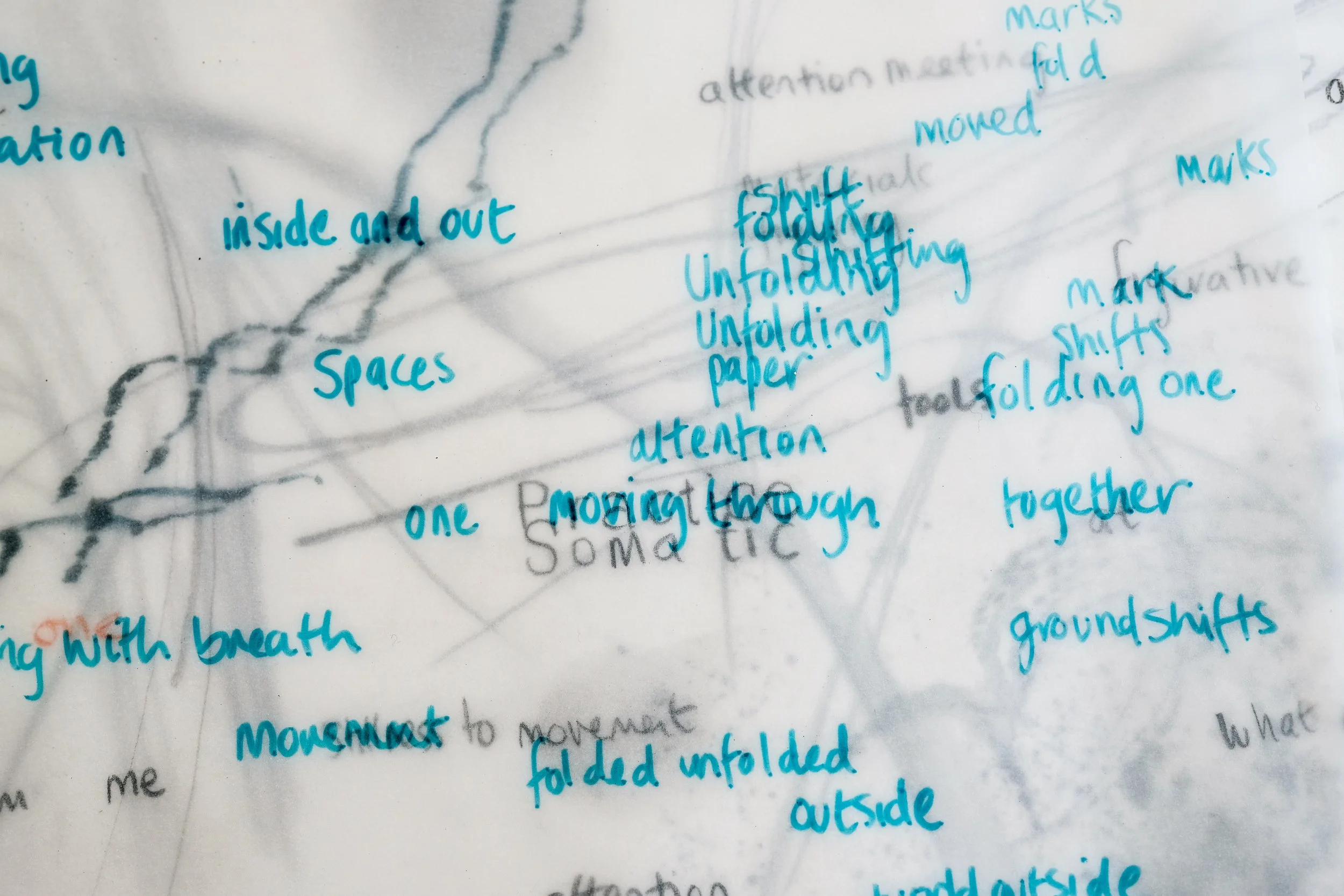

From 2020 until now, I realise that Órla has never precisely articulated her research question to me. She refers obliquely to it, in her references to the research and reading she does; in the scraps of words and images that she pulls into focus, assembles and reassembles as an aid to her investigations; in the work itself, wordless and undeniable, as she dives deeper and deeper down in order to surface her truth. In a world increasingly dominated by noise, speed, and digital saturation, her work offers us an antidote—a space of stillness where marks emerge from silence and return to it. She has honed a practice that values a deeper engagement with the intangible: presence, sensation, and the fleeting nature of experience. Her drawings are no longer visual representations of her world; they are exhalations, traces of presence, invitations to pause.